Today’s blog entry will be much shorter than Friday’s, for one simple reason: Class K “orange dwarf” stars are much less terrifying than Class M red dwarfs. That means there are fewer survival challenges and requirements for your characters.

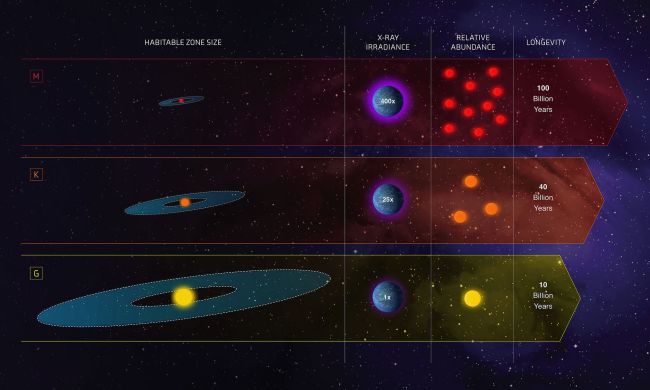

Class K stars are something of a “happy medium” between our own Sun and red dwarfs. Like red dwarfs, they’re more common and longer-lived than our own Sun. But because they burn somewhat hotter and brighter, their planets may not face the same dangers of extreme climate and cosmic radiation faced by life around red dwarfs.

Class K stars are three times more common in the universe than stars like our own Sun. They can live for 15 to 45 billion years – 1.5 to 4.5 times longer than our own Sun. They maintain stable habitable zones – meaning planets can stay in the same orbit without becoming too hot or too cold for liquid water to exist on their surface – for most of that time.

This combination of long lifespan and commonality led astronomers at the 2020 meeting of the American Astronomical Society to suggest that class K stars were the best stars to focus on in our search for life on other planets. The same attributes might make them the best place for us to look for homes for future space colonists.

It gets even better. Class K stars are less likely to release devastating solar flares than red dwarfs, and they also produce less DNA-damaging stellar radiation than hotter stars like our Sun. Planets in the habitable zone around these stars would orbit at a safe distance, and so would be able to maintain an Earthlike day-night cycle and a healthy magnetic field to protect their native life.

That also means that Earth-sized planets – those with human-friendly gravity – might do better around Class K stars. While planets orbiting red dwarfs may need to be bigger, with stronger gravity to hold onto their atmospheres and oceans, Class K stars should be able to be Earth-sized. This means that humans wouldn’t have to suffer from the life-shortening effects of higher gravity.

Does this make Class K stars less exciting? Well, yes. A little. Your characters are less likely to be killed by exposure to stellar radiation, or by the strain high gravity places on the heart, or by crash-landing in the eternal night of a tidally locked planet.

But they’re more likely to be able to build thriving cities and cultures, some of which may be longer-lived than our own Sun’s life cycle even allows. These stars may be good settings for planets that you want to be similar to Earth – but with an exotic twist. They should be capable of sustaining any biome or prevailing climate condition that has ever been found on Earth, including planets that are mostly desert, mostly ice, or covered by paradisal jungles and forests.

And don’t worry – if you want your colonists or alien life to have challenges to overcome, we’ll visit countless ways to do that in our later chapters looking at how a planet’s orbit and axial tilt can trigger periodic Ice Ages, periodic extreme climate change, and extreme seasons. Later, we’ll also investigate the impact of other mass extinction events that can be triggered by asteroid impacts, runaway volcanic activity, and runaway biological activity.

So what would life be like on a planet with a class K sun, compared to life on Earth?

The Aesthetics

As with red dwarf stars, Class K stars produce less blue light than our Sun. However, they also produce more blue light than red dwarfs, so the sky on planets orbiting Class K stars would likely range from white or grey on a planet orbiting a very cool (cooler stars are redder) class K star, to an earthlike pale blue.

As with all planets, a thicker, wetter atmosphere will likely result in a brighter-colored blue or greenish-blue sky, while a thinner atmosphere with fewer gas and water molecules to scatter light would likely appear darker.

As with red dwarfs, photosynthetic organisms that survive on class K stars are likely to be darker than plants and algae evolved on Earth. They may be black to very dark green as they scramble to soak up all available light from these dimmer stars.

Humans might find the warmer light of class K stars warm and homey, as we tend to associate golden sunlight and sunset colors with pleasant emotions. However, the relative lack of the color green and the muted color of the sky may feel a bit monochromatic to humans who are accustomed to the natural colors of Earth’s star with its greater output of blue light, and its plants which are more willing to reflect green light without absorbing it.

I know that some of you are working on designing life forms while others work on designing planets, so stay tuned next week for a dive into designing alien life. We’ll revisit the rest of the star types (the next class to cover is one you’re probably very familiar with, because our own Sun belongs to it!) later.

What are your burning questions about designing alien life forms? I’ll try to tackle them in the entries to come!